Pelvises I Have Known and Loved -Â by Gloria Lemay (Midwife)

Pelvises I Have Known and Loved -Â by Gloria Lemay (Midwife)

(© 2003 Midwifery Today, Inc. All rights reserved.If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy Midwifery Today magazine! Subscribe now! [Editor’s note: This article first appeared in Midwifery Today Issue 50, Summer 1999 and is also available online in Spanish.])

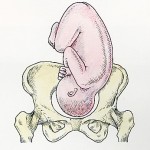

What if there were no pelvis? What if it were as insignificant to how a child is born as how big the nose is on the mother’s face? After twenty years of watching birth, this is what I have come to. Pelvises open at three stretch points—the symphisis pubis and the two sacroiliac joints. These points are full of relaxin hormones—the pelvis literally begins falling apart at about thirty-four weeks of pregnancy. In addition to this mobile, loose, stretchy pelvis, nature has given human beings the added bonus of having a moldable, pliable, shrinkable baby head. Like a steamer tray for a cooking pot has folding plates that adjust it to any size pot, so do these four overlapping plates that form the infant’s skull adjust to fit the mother’s body.

Every woman who is alive today is the result of millions of years of natural selection. Today’s women are the end result of evolution. We are the ones with the bones that made it all the way here. With the exception of those born in the last thirty years, we almost all go back through our maternal lineage generation after generation having smooth, normal vaginal births. Prior to thirty years ago, major problems in large groups were always attributable to maternal malnutrition (starvation) or sepsis in hospitals.

Twenty years ago, physicians were known to tell women that the reason they had a cesarean was that the child’s head was just too big for the size of the pelvis. The trouble began when these same women would stay at home for their next child’s birth and give birth to a bigger baby through that same pelvis. This became very embarrassing, and it curtailed this reason being put forward for doing cesareans. What replaced this reason was the post-cesarean statement: “Well, it’s a good thing we did the cesarean because the cord was twice around the baby’s neck.” This is what I’ve heard a lot of in the past ten years. Doctors must come up with a very good reason for every operation because the family will have such a dreadful time with the new baby and mother when they get home that, without a convincing reason, the fathers would be on the warpath. Just imagine if the doctor said honestly, “Well, Joe, this was one of those times when we jumped the gun—there was actually not a thing wrong with either your baby or your wife. I’m sorry she’ll have a six week recovery to go through for nothing.” We do know that at least 15 percent of cesareans are unnecessary but the parents are never told. There is a conspiracy among hospital staff to keep this information from families for obvious reasons.

In a similar vein, I find it interesting that in 1999, doctors now advocate discontinuing the use of the electronic fetal monitor. This is something natural birth advocates have campaigned hard for and have not been able to accomplish in the past twenty years. The natural-types were concerned about possible harm to the baby from the Doppler ultrasound radiation as well as discomfort for the mother from the two tight belts around her belly. Now in l999, the doctors have joined the campaign to rid maternity wards of these expensive pieces of technology. Why, you ask. Because it has just dawned on the doctors that the very strip of paper recording fetal heart tones that they thought proved how careful and conscientious they were, and which they thought was their protection, has actually been their worst enemy in a court of law. A good lawyer can take any piece of “evidence” and find an expert to interpret it to his own ends. After a baby dies or is damaged, the hindsight people come in and go over these strips, and the doctors are left with huge legal settlements to make. What the literature indicates now is that when a nurse with a stethoscope listens to the “real” heartbeat through a fetoscope (not the bounced back and recorded beat shown on a monitor read-out) the cesarean rate goes down by 50 percent with no adverse effects on fetal mortality rates.

Of course, I am in favour of the abolition of electronic fetal monitoring but it would be far more uplifting if this was being done for some sort of health improvement and not just more ways to cover butt in court.

Now let’s get back to pelvises I have known and loved. When I was a keen beginner midwife, I took many workshops in which I measured pelvises of my classmates. Bi-spinous diameters, sacral promontories, narrow arches—all very important and serious. Gynecoid, android, anthropoid and the dreaded platypelloid all had to be measured, assessed and agonized over. I worried that babies would get “hung up” on spikes and bone spurs that could, according to the folklore, appear out of nowhere. Then one day I heard the head of obstetrics at our local hospital say, “The best pelvimeter is the baby’s head.” In other words, a head passing through the pelvis would tell you more about the size of it than all the calipers and X-rays in the world. He did not advocate taking pelvic measurements at all. Of course, doing pelvimetry in early pregnancy before the hormones have started relaxing the pelvis is ridiculous.

One of the midwife “tricks” that we were taught was to ask the mother’s shoe size. If the mother wore size five or more shoes, the theory went that her pelvis would be ample. Well, 98 percent of women take over size five shoes so this was a good theory that gave me confidence in women’s bodies for a number of years. Then I had a client who came to me at eight months pregnant seeking a home waterbirth. She had, up till that time, been under the care of a hospital nurse-midwifery practise. She was Greek and loved doing gymnastics. Her eighteen-year-old body glowed with good health, and I felt lucky to have her in my practise until I asked the shoe size question. She took size two shoes. She had to buy her shoes in Chinatown to get them small enough—oh dear. I thought briefly of refreshing my rusting pelvimetry skills, but then I reconsidered. I would not lay this small pelvis trip on her. I would be vigilant at her birth and act if the birth seemed obstructed in an unusual way, but I would not make it a self-fulfilling prophecy. She gave birth to a seven-pound girl and only pushed about twelve times. She gave birth in a water tub sitting on the lap of her young lover and the scene reminded me of “Blue Lagoon” with Brooke Shields—it was so sexy. So that pelvis ended the shoe size theory forever.

One of the midwife “tricks” that we were taught was to ask the mother’s shoe size. If the mother wore size five or more shoes, the theory went that her pelvis would be ample. Well, 98 percent of women take over size five shoes so this was a good theory that gave me confidence in women’s bodies for a number of years. Then I had a client who came to me at eight months pregnant seeking a home waterbirth. She had, up till that time, been under the care of a hospital nurse-midwifery practise. She was Greek and loved doing gymnastics. Her eighteen-year-old body glowed with good health, and I felt lucky to have her in my practise until I asked the shoe size question. She took size two shoes. She had to buy her shoes in Chinatown to get them small enough—oh dear. I thought briefly of refreshing my rusting pelvimetry skills, but then I reconsidered. I would not lay this small pelvis trip on her. I would be vigilant at her birth and act if the birth seemed obstructed in an unusual way, but I would not make it a self-fulfilling prophecy. She gave birth to a seven-pound girl and only pushed about twelve times. She gave birth in a water tub sitting on the lap of her young lover and the scene reminded me of “Blue Lagoon” with Brooke Shields—it was so sexy. So that pelvis ended the shoe size theory forever.

Another pelvis that came my way a few years ago stands out in my mind. This young woman had had a cesarean for her first childbirth experience. She had been induced, and it sounded like the usual cascade of interventions. When she was being stitched up after the surgery her husband said to her, “Never mind, Carol, next baby you can have vaginally.” The surgeon made the comment back to him, “Not unless she has a two pound baby.” When I met her she was having mild, early birth sensations. Her doula had called me to consult on her birth. She really had a strangely shaped body. She was only about five feet, one inch tall, and most of that was legs. Her pregnant belly looked huge because it just went forward—she had very little space between the crest of her hip and her rib cage. Luckily her own mother was present in the house when I first arrived there. I took her into the kitchen and asked her about her own birth experiences. She had had her first baby vaginally. With her second, there had been a malpresentation and she had undergone a cesarean. Since the grandmother had the same body-type as her daughter, I was heartened by the fact that at least she had had one baby vaginally. Again, this woman dilated in the water tub. It was a planned hospital birth, so at advanced dilation they moved to the hospital. She was pushing when she got there and proceeded to birth a seven-pound girl. She used a squatting bar and was thrilled with her completely spontaneous birth experience. I asked her to write to the surgeon who had made the remark that she couldn’t birth a baby over two pounds and let him know that this unscientific, unkind remark had caused her much unneeded worry.

Another group of pelvises that inspire me are those of the pygmy women of Africa. I have an article in my files by an anthropologist who reports that these women have a height of four feet, on average. The average weight of their infants is eight pounds! In relative terms, this is like a woman five feet six giving birth to a fourteen-pound baby. The custom in their villages is that the woman stays alone in her hut for birth until her membranes rupture. At that time, she strolls through the village and finds her midwives. The midwives and the woman hold hands and sing as they walk down to the river. At the edge of the river is a flat, well-worn rock on which all the babies are born. The two midwives squat at the mother’s side while she pushes her baby out. One midwife scoops up river water to splash on the newborn to stimulate the first breath. After the placenta is birthed the other midwife finds a narrow place in the cord and chews it to separate the infant. Then, the three walk back to join the people. This article has been a teaching and inspiration for me.

That’s the bottom line on pelvises—they don’t exist in real midwifery. Any baby can slide through any pelvis with a powerful uterus pistoning down on him/her.

That’s the bottom line on pelvises—they don’t exist in real midwifery. Any baby can slide through any pelvis with a powerful uterus pistoning down on him/her.

Gloria Lemay is a private birth attendant in Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

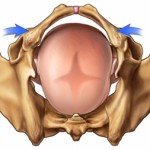

A gynecoid pelvis is oval at the inlet, has a generous capacity and wide subpubic arch. This is the classical female pelvis. Pelvic brim is a transverse ellipse (nearly a circle) Most favorable for delivery.The gynecoid pelvis (sometimes called a “true female pelvis”) is found in about 50% of the women in America. It is the “classic” form that we associate with women and has an anteroposterior diameter just slightly less than the transverse diameter. Lucy Lawless of Xena, Warrior Princess fame has a classic gynecoid pelvis. Women like this tend to look…like women. They are shapely and curvy. They tend to hold fat around the thighs more so than the mid-riff. They can have a flat stomach without                             really dropping body fat levels low enough to cause some “female problems.”

A gynecoid pelvis is oval at the inlet, has a generous capacity and wide subpubic arch. This is the classical female pelvis. Pelvic brim is a transverse ellipse (nearly a circle) Most favorable for delivery.The gynecoid pelvis (sometimes called a “true female pelvis”) is found in about 50% of the women in America. It is the “classic” form that we associate with women and has an anteroposterior diameter just slightly less than the transverse diameter. Lucy Lawless of Xena, Warrior Princess fame has a classic gynecoid pelvis. Women like this tend to look…like women. They are shapely and curvy. They tend to hold fat around the thighs more so than the mid-riff. They can have a flat stomach without                             really dropping body fat levels low enough to cause some “female problems.” A platypoid pelvis is flattened at the inlet and has a prominent sacrum. The subpubic arch is generally wide but the ischial spines are prominent. This pelvis favors transverse presentations. Pelvic brim is transversekidney shape. The platypelloid pelvis is very short (almost like a “flattened gynecoid shape”). Only about 3% of women have a true and pure pelvis of this type. Women having a platypelloid pelvis tend to carry a lot of weight in the lower abdomen. It’s very difficult for these women to have really flat abdomens without getting body fat levels down into the                                        single digits.

A platypoid pelvis is flattened at the inlet and has a prominent sacrum. The subpubic arch is generally wide but the ischial spines are prominent. This pelvis favors transverse presentations. Pelvic brim is transversekidney shape. The platypelloid pelvis is very short (almost like a “flattened gynecoid shape”). Only about 3% of women have a true and pure pelvis of this type. Women having a platypelloid pelvis tend to carry a lot of weight in the lower abdomen. It’s very difficult for these women to have really flat abdomens without getting body fat levels down into the                                        single digits. An anthropoid pelvis is, like the gynecoid pelvis, basically oval at the inlet, but the long axis is oriented vertically rather than side to side.Subpubic arch may be slightly narrowed. This pelvis favors occiput posterior presentations. Pelvic brim is an anteroposterior ellipse, Gynecoid pelvis turned 90 degrees, Narrow ischial spines. Much more common in black womenThe anthropoid pelvis is very long and almost “ovoid” in shape. It is more common in non-white females (it makes up about 25% of pelvic type in white women and close to 50% in non-white women). Women who have such a pelvis shape tend to have “larger rear ends” and may carry a lot of adipose tissue/weight in the buttocks as well as in the abdomen. These women can have a flat stomach with some real effort (they may have to drop body fat levels down a bit lower than women with the other two aforementioned pelvis types, but it’s “doable”).

An anthropoid pelvis is, like the gynecoid pelvis, basically oval at the inlet, but the long axis is oriented vertically rather than side to side.Subpubic arch may be slightly narrowed. This pelvis favors occiput posterior presentations. Pelvic brim is an anteroposterior ellipse, Gynecoid pelvis turned 90 degrees, Narrow ischial spines. Much more common in black womenThe anthropoid pelvis is very long and almost “ovoid” in shape. It is more common in non-white females (it makes up about 25% of pelvic type in white women and close to 50% in non-white women). Women who have such a pelvis shape tend to have “larger rear ends” and may carry a lot of adipose tissue/weight in the buttocks as well as in the abdomen. These women can have a flat stomach with some real effort (they may have to drop body fat levels down a bit lower than women with the other two aforementioned pelvis types, but it’s “doable”). An android pelvis is more triangular in shape at the inlet, with a narrowed subpubic arch. Larger babies have difficulty traversing this pelvis as the normal areas for fetal rotation and extension are blocked by boney prominences. Smaller babies still squeeze through. (Male type) Pelvic brim is triangular Convergent Side Walls (widest posteriorly) Prominent ischial spines, Narrow subpubic arch, More common in white womenThe android pelvis (sometimes called a “true make pelvis”) is found in about 20% of American women. Women who happen to have such a pelvis tend to have “flat rear ends.” Many of the truly “waifish women” we see so prominently in modeling today have this type of pelvis. It’s not necessarily a good thing for a woman to have such a pelvic shape, as most of these women will end up having a Cesarean Section if they want to have children. Women with this shape of pelvis have virtually no real difficulty in achieving a flat stomach—no more than the “average male”—because their pelvises are shaped like an average male.

An android pelvis is more triangular in shape at the inlet, with a narrowed subpubic arch. Larger babies have difficulty traversing this pelvis as the normal areas for fetal rotation and extension are blocked by boney prominences. Smaller babies still squeeze through. (Male type) Pelvic brim is triangular Convergent Side Walls (widest posteriorly) Prominent ischial spines, Narrow subpubic arch, More common in white womenThe android pelvis (sometimes called a “true make pelvis”) is found in about 20% of American women. Women who happen to have such a pelvis tend to have “flat rear ends.” Many of the truly “waifish women” we see so prominently in modeling today have this type of pelvis. It’s not necessarily a good thing for a woman to have such a pelvic shape, as most of these women will end up having a Cesarean Section if they want to have children. Women with this shape of pelvis have virtually no real difficulty in achieving a flat stomach—no more than the “average male”—because their pelvises are shaped like an average male.

Pelvises I Have Known and Loved

Saturday, June 13th, 2009(© 2003 Midwifery Today, Inc. All rights reserved.If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy Midwifery Today magazine! Subscribe now! [Editor’s note: This article first appeared in Midwifery Today Issue 50, Summer 1999 and is also available online in Spanish.])

What if there were no pelvis? What if it were as insignificant to how a child is born as how big the nose is on the mother’s face? After twenty years of watching birth, this is what I have come to. Pelvises open at three stretch points—the symphisis pubis and the two sacroiliac joints. These points are full of relaxin hormones—the pelvis literally begins falling apart at about thirty-four weeks of pregnancy. In addition to this mobile, loose, stretchy pelvis, nature has given human beings the added bonus of having a moldable, pliable, shrinkable baby head. Like a steamer tray for a cooking pot has folding plates that adjust it to any size pot, so do these four overlapping plates that form the infant’s skull adjust to fit the mother’s body.

Every woman who is alive today is the result of millions of years of natural selection. Today’s women are the end result of evolution. We are the ones with the bones that made it all the way here. With the exception of those born in the last thirty years, we almost all go back through our maternal lineage generation after generation having smooth, normal vaginal births. Prior to thirty years ago, major problems in large groups were always attributable to maternal malnutrition (starvation) or sepsis in hospitals.

Twenty years ago, physicians were known to tell women that the reason they had a cesarean was that the child’s head was just too big for the size of the pelvis. The trouble began when these same women would stay at home for their next child’s birth and give birth to a bigger baby through that same pelvis. This became very embarrassing, and it curtailed this reason being put forward for doing cesareans. What replaced this reason was the post-cesarean statement: “Well, it’s a good thing we did the cesarean because the cord was twice around the baby’s neck.” This is what I’ve heard a lot of in the past ten years. Doctors must come up with a very good reason for every operation because the family will have such a dreadful time with the new baby and mother when they get home that, without a convincing reason, the fathers would be on the warpath. Just imagine if the doctor said honestly, “Well, Joe, this was one of those times when we jumped the gun—there was actually not a thing wrong with either your baby or your wife. I’m sorry she’ll have a six week recovery to go through for nothing.” We do know that at least 15 percent of cesareans are unnecessary but the parents are never told. There is a conspiracy among hospital staff to keep this information from families for obvious reasons.

In a similar vein, I find it interesting that in 1999, doctors now advocate discontinuing the use of the electronic fetal monitor. This is something natural birth advocates have campaigned hard for and have not been able to accomplish in the past twenty years. The natural-types were concerned about possible harm to the baby from the Doppler ultrasound radiation as well as discomfort for the mother from the two tight belts around her belly. Now in l999, the doctors have joined the campaign to rid maternity wards of these expensive pieces of technology. Why, you ask. Because it has just dawned on the doctors that the very strip of paper recording fetal heart tones that they thought proved how careful and conscientious they were, and which they thought was their protection, has actually been their worst enemy in a court of law. A good lawyer can take any piece of “evidence” and find an expert to interpret it to his own ends. After a baby dies or is damaged, the hindsight people come in and go over these strips, and the doctors are left with huge legal settlements to make. What the literature indicates now is that when a nurse with a stethoscope listens to the “real” heartbeat through a fetoscope (not the bounced back and recorded beat shown on a monitor read-out) the cesarean rate goes down by 50 percent with no adverse effects on fetal mortality rates.

Of course, I am in favour of the abolition of electronic fetal monitoring but it would be far more uplifting if this was being done for some sort of health improvement and not just more ways to cover butt in court.

Now let’s get back to pelvises I have known and loved. When I was a keen beginner midwife, I took many workshops in which I measured pelvises of my classmates. Bi-spinous diameters, sacral promontories, narrow arches—all very important and serious. Gynecoid, android, anthropoid and the dreaded platypelloid all had to be measured, assessed and agonized over. I worried that babies would get “hung up” on spikes and bone spurs that could, according to the folklore, appear out of nowhere. Then one day I heard the head of obstetrics at our local hospital say, “The best pelvimeter is the baby’s head.” In other words, a head passing through the pelvis would tell you more about the size of it than all the calipers and X-rays in the world. He did not advocate taking pelvic measurements at all. Of course, doing pelvimetry in early pregnancy before the hormones have started relaxing the pelvis is ridiculous.

Another pelvis that came my way a few years ago stands out in my mind. This young woman had had a cesarean for her first childbirth experience. She had been induced, and it sounded like the usual cascade of interventions. When she was being stitched up after the surgery her husband said to her, “Never mind, Carol, next baby you can have vaginally.” The surgeon made the comment back to him, “Not unless she has a two pound baby.” When I met her she was having mild, early birth sensations. Her doula had called me to consult on her birth. She really had a strangely shaped body. She was only about five feet, one inch tall, and most of that was legs. Her pregnant belly looked huge because it just went forward—she had very little space between the crest of her hip and her rib cage. Luckily her own mother was present in the house when I first arrived there. I took her into the kitchen and asked her about her own birth experiences. She had had her first baby vaginally. With her second, there had been a malpresentation and she had undergone a cesarean. Since the grandmother had the same body-type as her daughter, I was heartened by the fact that at least she had had one baby vaginally. Again, this woman dilated in the water tub. It was a planned hospital birth, so at advanced dilation they moved to the hospital. She was pushing when she got there and proceeded to birth a seven-pound girl. She used a squatting bar and was thrilled with her completely spontaneous birth experience. I asked her to write to the surgeon who had made the remark that she couldn’t birth a baby over two pounds and let him know that this unscientific, unkind remark had caused her much unneeded worry.

Another group of pelvises that inspire me are those of the pygmy women of Africa. I have an article in my files by an anthropologist who reports that these women have a height of four feet, on average. The average weight of their infants is eight pounds! In relative terms, this is like a woman five feet six giving birth to a fourteen-pound baby. The custom in their villages is that the woman stays alone in her hut for birth until her membranes rupture. At that time, she strolls through the village and finds her midwives. The midwives and the woman hold hands and sing as they walk down to the river. At the edge of the river is a flat, well-worn rock on which all the babies are born. The two midwives squat at the mother’s side while she pushes her baby out. One midwife scoops up river water to splash on the newborn to stimulate the first breath. After the placenta is birthed the other midwife finds a narrow place in the cord and chews it to separate the infant. Then, the three walk back to join the people. This article has been a teaching and inspiration for me.

Gloria Lemay is a private birth attendant in Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

Posted in Pelvic Bone Commentary | Comments Off on Pelvises I Have Known and Loved